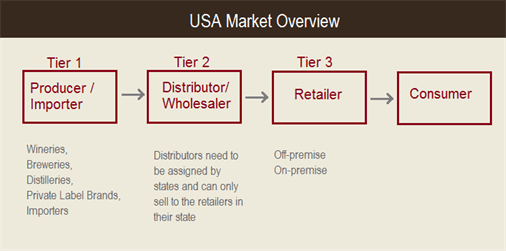

We have explored the origins, mechanics, and potential future state of the U.S. three-tiered distribution system for wine (i. retailer/importer, ii. distributor/wholesaler, iii. retailer) as well as the role of third-party logistics firms and third-party marketing firms.

However, much of this discussion has been from the perspective of one or more of those players in the ecosystem, all of whom are a 'supplier' of some kind of from the perspective of the end consumer who drinks the wine. We haven't explored just how this regulatory and operational nightmare translates into end-user experience.

I decided to answer this question empirically by attempting to complete three types of wine purchases:

- Replicate one of the recent editions of Eric Asimov's "Wine School"

- NYT wine critic recommendations of wine varietals or regions to explore at home with friends, with recommendations and discussion.

- In this case, "Madeira."

- Purchase a variety of Georgian (Republic of Georgia) wines

- For research purposes for midterm project...

- Horizontal (varietals, producers) and vertical (from some producers I know are good)

- Emphasis on variety

- Pick up extra bottles of wines I like along the way

- For example, a few extra bottles of Scharffenberger's non-vintage Brut Andersen Valley sparkling, if they could be had for same or less than a local retailer.

This ended happily (enough) in that wine will be delivered to me. But the process was extremely painful, and illuminating. I had only ever ordered wine

delivered before as a gift to others, and never when I was trying to be especially thoughtful or picky about the selection. It proved impossible to complete all three types of purchases locally,

or with the same online retailer, and was frustrating in surprising ways.

My efforts to give retailers money in exchange for wine was stymied by:

- Weak eCommerce platforms

- For example, losing my cart; miscalculating shipping; etc.

- Inconsistent transparency on regulatory operating licenses

- Many caveats and "at your own risks" were employed to magic away some of the diligence that might have been called for in shipping to my jurisdiction.

- Extreme heterogeneity of assortment

- Especially because some products I wanted were more unusual, the likelihood of one store carrying them all was very low.

- In a surprise however, many categories were not carried at all, or were carried with minimal assortment.

- Resources such as wine-searcher.com, while helpful, relied on paid placement or sponsored results, and had data issues that could be cumbersome - ranking 100 "half-bottles" as cheapest options instead of the first full 750ml bottle, for example, or not taking into account shipping costs for a UK retailer that imports from France (and may not ship to the U.S.)!

- High shipping costs and unclear pricing models

- Shipping costs for firms not based in CA, shipping to CA, were often quite high

- Could often easily guess if a retailer used WineDirect or another wine-focused 3PL vendor; many or most, however, used stores or local warehousing for fulfillment.

- Ship costs varied in ambiguous, non-transparent ways when shipping to commercial vs. residential and when adding bottles ("If a case has a discount, does it matter if there are 2 half-bottles or 1 full bottle?")

In this regard third-party marketing firms, whether search engines like 1000 Corks and Wine-Searcher, or review sites like CellarTracker and Vivino, didn't solve the entire customer discovery journey. I was willing to exercise considerable flexibility, but the lack of an efficient marketplace was a tremendous impediment to the experience and indeed basket size. It was further difficult to comparison-shop as shipping would not be adequately priced; a different of $3 per bottle gross could become a difference of $10 net depending on how shipping was calculated.

Ultimately, this information problem should be solvable. To some extent it is also a question of expectation-setting. In researching Georgian wines, I consulted a variety of different government or industry-sponsored bodies (from distributors, to importers, to trade associations) each of whom listed different collections of retailers that carried or could ship relevant wines. But on closer observation and in some cases phone calls, what this meant was that XYZ Wine Retailer "had carried ABC wine... 2 years ago... and sometimes has it in stock" (or a similar story). At best, they may have carried only a subset of the selection. When searching for the Madeira tasting wines -- 3 Madeiras, made in the same edition by the same producer -- the cheapest website with the best customer service and user interface had only 2 of the 3 sought-after wines, with no ready substitute... pushing me to another vendor entirely.

All of this points to a tremendous opportunity from consolidation -- not just for market power, but for real returns to consumers who are looking to explore more of the 100,000s of SKUs available in the U.S. at any given time. What good does it do to educate consumers and bring them new wines, and give them an app to remember the wine, if they can never buy it again? A winery can hold an audience through wine clubs, but for consumers looking for a modern retail buying experience there remains tremendous room to improve.

P.S. to readers here, I have ~20 bottles of wine arriving in the next week as a result of my research here, so please help me drink it.